|

Mechanics Hall “THE WORCESTER ORGAN” |

Photography this page by Will Sherwood

Other related links: WORCESTER ORGANS • MUNICIPAL ORGANS

Photography this page by Will Sherwood

Other related links: WORCESTER ORGANS • MUNICIPAL ORGANS

| E & G G Hook Opus 334 1864 52 stops, 64 ranks, 3504 pipes Wind supply History Bibliography The Historical Organ in America, Lynn Edwards, ed., The Westfield Center, 1992 Preserving the Acoustics of Mechanics Hall: a Restoration Without Compromising Acoustical Integrity,” W J Cavanaugh, Technology & Conservation (Fall, 1980). Registration Chart Template for Organists |

Specification

I Choir (C-a3, 58)

II Great (C-a3, 58)

III Swell (C-a3, 58)

IV Solo (C-a3, 58)

Pedale (C-f1, 30, straight, flat pedalboard

Couplers

* Barker assist; (no way to disable Barkers) Combination pedals

Piano Swell

Forte Swell

Great to Pedale (reversible)

Pedale (brings on Diapason 16' and Pedale II stops' controls)

Piano Great

Forte Great

Piano Choir

Forte Choir

Accessories

Swell tremulant

Bellows signal (not used)

Pedale Check

Ventil 1 (Open Diapason 16')

Ventil 2 (Pedale II chest)

|

|

|

Falling into disuse after the depression years, the Worcester County Mechanics Association restored it during the 1970s to its original beauty and excellent acoustics. Soon thereafter, the 1864 Hook organ was restored by Fritz Noack under the leadership of an AGO restoration committee headed by the late Stephen Long. Many fundraisers, such as selling organ chamber dust(!), were held to fund the project.

The organ, with chamber openings cloistered by large oil paintings of early American leaders, is the largest nineteenth century American concert hall organ that can still be heard in its original location. Additional building renovations were completed in 1990, and major maintenance is scheduled for the fall of 2002. Seating almost 1400 with a 1000-square-foot stage, Mechanics Hall retains its original purpose as a multi-use auditorium for concerts, business functions, receptions, and dinners– a perfect location for a wedding, or a brown-bag organ recital. The 100-ft-long hall provides visual and acoustical intimacy with no sound-absorbing materials used in the surfaces (except seat cushions). The reverberation time at a concert with full audience, but no orchestra on stage, is 1.6 seconds. Its principal deficiency is the flat main floor which necessitates neck stretching to view performances. Architect: original hall, Elbridge Boyden; 1970s building renovation, Anderson Notter Finegold, Inc.; 1990s renovation, Lamoureaux Pagano & Associates, Inc.; Acoustical consultants (both renovations) Cavanaugh Tocci Associates, Inc.; Sound Consultants: David H Kaye.

|

The Worcester Organ: A Retrospective

– The Rev. Richard F. Jones, Mechanics Hall Curator and Development Officer 1983-1991

There is an arch adorned with cherubs that has been hidden since 1864 behind the tops of the central façade pipes of the organ in Mechanics Hall. It is an artifact of the seven year period when there was no pipe organ in the Great Hall. In 1857, Mechanics Hall was built to house the activities of the Worcester County Mechanics Association and as a place for the community to gather for lectures, concerts, and social events. Space was created for a pipe organ, but there was no money. Until Ichabod Washburn’s gift of $1000 in 1863 spurred his fellow industrialists to give the funds necessary to build and install an organ, twisted Solomonic columns and false façade pipes filled the space where the organ is now. (The columns exist and are in storage at the Worcester Historical Museum.)

A pipe organ was a standard accoutrement of large concert halls in nineteenth century America. Orchestral concerts were rare. In Worcester, as Dvorak lamented when he conducted here, orchestras were heard only one week each autumn when the Worcester Music Festival convened. Pipe organs filled the gap. With their many different sounds, they allowed for the performance of music people would otherwise be unable to hear.

It is probably no coincidence that funding for an organ in Mechanics Hall was made available the same year the magnificent Walcker organ was installed in the Boston Music Hall. Worcester can be justly proud of its contributions to American life, from the first National Women’s Rights Convention to the suits that astronauts donned for space flights. It was an important goal of the Mechanics Association that every detail in the Hall, including the pipe organ, be American made.

So the Mechanics Association commissioned the finest American organ builders at the time, E. and G.G. Hook, to create the largest pipe organ that had ever been constructed in the United States. The choice of an American firm was significant. At the organ’s dedication, its “superiority over all other organs in this country” was claimed, a poke at Boston and its foreign-built Walcker instrument. The Hook brothers were probably eager to show what their firm was capable of as well, and provided the instrument essentially at cost.

However, the Hooks were not pleased with the result. The records of the Mechanics Association recount the battle they had with the Association’s board of directors. Aware that the sound and impact of the organ would be compromised by its chambered location, they pleaded with the board to bring the organ’s Great and Solo divisions out into the concert hall, with the Choir and Pedal projecting outward as well from twin cases where the portraits of Lincoln and Washington are today.

Initially, the Hall’s remarkable architect, Elbridge Boyden, who designed the current organ façade, sided with the board. Eventually, the Hooks won him over, and Boyden pressed their case. (Boyden deserves a separate essay. Half a century before Boston’s Symphony Hall was constructed, Boyden employed all the elements of design that made Symphony Hall a landmark. He also created ventilation systems that moistened the air in winter and cooled it in summer.)

The board of directors did not budge. The Hooks’ scheme would cost too much. The organ remained deep in its chamber, the majestic sound its builders intended forever muffled. As significant as the organ in Mechanics Hall was, the Hooks never promoted it.

Nonetheless, Worcester loved the organ, dubbed “The Worcester Organ,” because of the many contributions toward its installation from citizens of the city. Following its dedication in October 1864, B. D. Allen, later to be a founding member of the American Guild of Organists, was named the Hall’s primary organist. He instituted a series of free concerts for schoolchildren that were the inspiration of the “Brown Bag Concerts” conceived a hundred years later. Those who funded the organ in 1863 had made free concerts a condition of their gift.

For five or six years after the organ was installed, it was the centerpiece of concert after concert. By the 1870s, though, “The Worcester Organ” had fallen into disuse, and was heard primarily at the week-long music festivals. In 1889, and with minimal notice, the Mechanics Association asked George S. Hutchings, formerly of Hook and Hastings, to perform major repairs and give the instrument a thorough cleaning in advance of that year’s Music Festival. This work included repitching the pipes from “Boston pitch” A=449 (one note sharp) to A=435, just flat of today’s A=440 worldwide standard.

In 1914, Hook and Hastings made significant alterations and, nine years later, George W. Reed electrified the action and introduced other “improvements.” The pattern of neglect and last-minute refurbishment continued until the Music Festival moved to the new Memorial Auditorium in 1933.

In the ensuing forty years, the organ was hardly ever heard, George Faxon presenting the only recital of note in 1961. Mechanics Hall relied on wrestling matches and roller skating to pay the bills. I remember coming to the hall to roller skate when I was in high school. The building, frankly, smelled like a rest room in a bus station, and decades of dust and dirt obscured the glories of the Great Hall. There was a proposal to tear down Mechanics Hall, and replace it with a parking lot. It nearly succeeded.

Enter Julie Chase Fuller, a popular local radio show host, who had become president of the Mechanics Association. She saw the awareness and appreciation of history engendered by the nation’s bicentennial as an opportunity and, with the Worcester Heritage Society and Richard C. Steele of the Telegram & Gazette, began a campaign to restore Mechanics Hall. No one was better than Julie Chase Fuller at raising funds from rich and important people. Mrs. Fuller wanted the organ restored, too, and enlisted the help of the Worcester Chapter, American Guild of Organists.

Bids were received. Andover Organ Company, which had restored more Hook organs than anyone else, submitted the lowest bid. However, because Fritz Noack proposed to re-create the instrument as it was in 1864, the contract was awarded to Noack Organ Co. Stephen Long, chair of the organ restoration committee, led his committee to spearhead the oversight and rededication concert celebrations.

As was the case when the Hall was built, there wasn’t enough money. Mechanics Hall, restored and resplendent, reopened in 1977. The organ was silent. By 1980, funding was in place, and Noack went to work. On September 25 and 26, 1982, the organ was re-dedicated in two concerts utilizing only Worcester musicians, echoing the parochial pride of 1864. The concerts played to packed houses and generated a memorable headline in the newspaper: “Mechanics Hall Organ Rededicated: Worcester Pride Bursts Forth.”

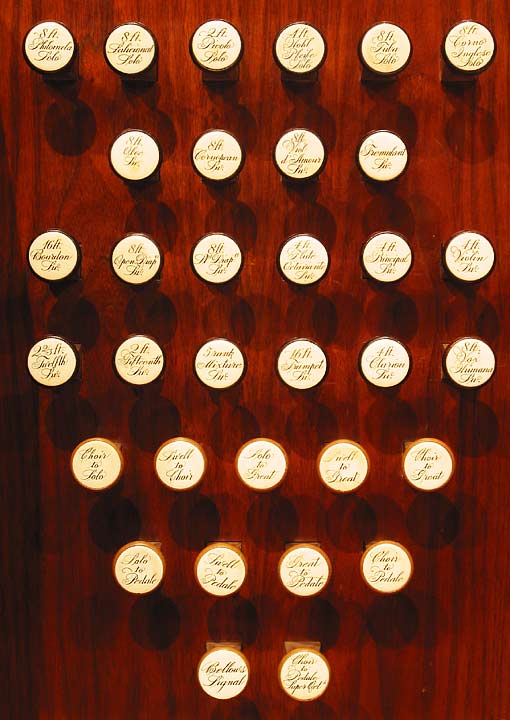

Fritz Noack executed a remarkable restoration. A more accurate restoration has probably never occurred. For example, there was no clear photo of the original console. Fritz re-created what he thought had been there. In 1985, I attended a meeting at GAR Hall on Pearl Street. I noticed a photograph of a group of Civil War veterans sitting on the stage of Mechanics Hall. In the center of the photograph was the original console of the Worcester Organ. This photograph is the only one of the original console close-up in existence. Fritz had gotten everything right. On the basis of research and intuition, he re-created the console exactly as it was, down to the last stop-knob and combination pedal.

In re-creating the original action, Fritz also unintentionally restored the insufficiencies of the instrument. Despite the use of the Barker Lever to assist the Great division, the action was heavy, and, in some respects, almost unplayable. Those who played the organ between 1982 and 1989 will remember the Herculean effort required to play on the Swell and the Choir, particularly when they were coupled. The restored double-shutters on the Swell severely limited its effectiveness. The same complaints were voiced in the nineteenth century.

The dry heat of the restored Mechanics Hall didn’t help. Elbridge Boyden had originally installed an innovative system to humidify the Hall. His successors in the 1970s were not as prescient. The air was so dry, the keyboards of the organ froze during the heating season, and the hundreds of leather nuts that regulated its action shriveled. The soundboard of the Hall’s previous Steinway also cracked.

The Worcester Organ was busy in the years following its restoration. Between 1983 and 1987, thirteen free “Brown Bag” organ recitals held on Wednesdays at noon attracted a thousand people for each concert, making the series one of the most popular organ concerts in the United States. The Fuller International Organ Festival in 1985 attracted attendees from more than a dozen countries. Simon Preston appeared at a Worcester Music Festival concert, and a formal evening series presented Peter Hurford and David Higgs among other luminaries. An organ education program was designed in cooperation with the Worcester Public Schools.

Because it was my job to promote the organ as well as oversee its maintenance, I did make some changes. The first was to remove the inner set of swell shades. The second was to try a new seating configuration for recitals. I left as much of the center part of the Mechanics Hall floor as possible empty to allow for more reflective surface.

As the organ approached its 125th anniversary in 1989, I oversaw important changes. The care of the organ was transferred to the Andover Organ Company, and Robert C. Newton in particular. No one knew Hook organs as well as Bob, or had restored as many. Straightaway, Bob replaced most of the leather nuts on the Barker Lever.

Bob installed relief pallets in the Hook style on the Swell and Choir. Relief pallets are tiny pneumatic assists for each key. The Hooks had begun to use them shortly after they built the Mechanics Hall organ.

Just this month through a generous grant from the Fuller Foundation, a second blower (electric air pump supplying wind pressure for the pipes) was added so that the organ’s pitch and volume would not sag when many notes and many stops were used for a chord held more than a few seconds. This second wind for the organ resolves one of the perennial problems with supplying it enough air to power all its pipes.

We are all grateful that Mechanics Hall’s board’s commitment and prudent management has ensured the preservation of the Hall and its organ, but the heavy rental schedule that keeps the Hall afloat also limits time available for organ rehearsal and performance.

Nonetheless, when the organ is heard, the sound is unique, not perhaps the sound the Hooks originally desired, but a sound that has come down to us one hundred and fifty years later almost exactly as it was, and that is eminently worth celebrating. The Worcester Organ Concert Series was begun in 2007 to showcase the instrument in concert, and the organ is used at other times during the year at graduation ceremonies, memorial services, and wedding ceremonies and it is a focal point of the Concerts for Kids: Introduction to American Composers concert program. It’s not able to be used every week for sure, but its use is commendable for a non-church organ and for continuing to offer free concerts for the public.

A final note: The one thing the organ does best is the thing it has done least. In recordings, the organ is everything the Hooks wanted and more. But only a handful of recordings have featured the instrument. My hope, on this 150th anniversary, is that the extraordinary sounds of this organ, among the finest the Hooks ever produced, will be captured and shared with a wider audience. They deserve to be heard.

– RFJConcert History

Since the restoration of the “Worcester Organ” was completed in 1982, there have been only six concerts [as of 2017] that have featured the instrument in a major orchestral role. The Poulenc Concerto for Organ and Orchestra has been performed three times by the former Worcester Orchestra with organ soloists Barclay Wood (1982), Catherine Crozier (1983); and Simon Preston (1985). James David Christie was soloist for the Poulenc with the Boston Artists Orchestra in 1989 in a concert celebrating the organ’s 125th anniversary. Mr. Christie also performed Guilmant’s Symphony I for Organ and Orchestra at that concert, the third performance at Mechanics Hall, the first being in 1882 when the work received it United States premiere. Stephen Pinel was at the organ for a 1987 performance of the Guilmant with the Bach Society of Worcester, Stephen Long, conductor. The most popular work for organ and orchestra, Saint-Saens “Organ Symphony,” has been heard only once, in 1983 with Holyoke organist Gilles Hebert, soloist, and the Eastern Connecticut Symphony Orchestra conducted by Dr. Paul Shannon. The Worcester Organ has, of course, been used with smaller ensembles and in performances of major works requiring it, including the Brahms Requiem, Strauss Also Sprach Zarathrustra, and Holst’s The Planets.

One additional note — the bellows of the Worcester Organ can still be pumped by hand, as they were at the 1989 recreation of the original dedicatory recital, when football players from Worcester Academy, a school associated with organ benefactor Ichabod Washburn, were recruited for that task. Few know that the bellows-pumps were discretely employed at the 1983 performance of the Saint-Saens, because the wind supply at that time was inadequate for the final chord without assistance.

Editor’s note: A few years ago, a second organ blower was installed to fully wind the Hook in all Tutti circumstances to unleash its full aerobic capacity without sag [WS].

Richard F. Jones, 2017

1991 Restoration Report by Fritz Noack (PDF link)

Picture Gallery

LEFT JAMB

RIGHT JAMB

Center of facade, looking upward

Square rails and stop lever mechanisms directly behind console

Fieldstone weights for main bellows

Tracker transports directly behind console

Pedal division pipes

Ready to pump manually if needed

Picture attached to a structural support, inside chamber

Rumor has it that this is a Hook grandson, but we think he had something to do with chickens

Photos from Sept. 2003 Brown Bag for Kids held at Mechanics Hall

Maria Ferrante, soprano; Betsy Northrupe, narrator; Will Sherwood, organ

E & G G Hook Opus listings surrounding Mechanics Hall’s installation:

1829, Opus 1. Danvers, MA, Unitarian, 1 manual.

. . .

1863, Opus 327. Cleveland, OH, Ursuline Convent. 1 manual. 12 registers.

1863, Opus 328. Bucksport, ME, Elm Street Congregational. 2 manuals. 14 ranks.

1863, Opus 329. Woonsocket, RI, St. James’ Episcopal. 2 manuals. 21 registers.

1863, Opus 330. Lafayette, IN, Second Presbyterian. 2 manuals. 26 registers.

1863, Opus 331. Hebron, ME, Tobie, R. C. residence. 2 manuals. 17 stops.

1863, Opus 332. Wellfleet, MA, Methodist. 2 manuals. 25 registers.

1864, Opus 333. Rochester, NY, Central Presbyterian. 3 manuals. 46 registers.

1864, Opus 334. Worcester, MA, Mechanics Hall. 4 manuals. 64 ranks.

1864, Opus 335. Boston, MA, Meionian Hall, Tremont Temple. 2 manuals. 25 registers.

1864, Opus 336. Pittsfield, NH, St. Stephen’s Episcopal. 1 manual. 8 registers.

1864, Opus 337. Rockford, IL, Second Congregational. 2 manuals. 27 registers.

1864, Opus 338. Sherborn, MA, Pilgrim United Church of Christ. 2 manuals. 18 ranks.

1864, Opus 339. Philadelphia, PA, Tabernacle Baptist. 2 manuals. 31 registers.

1864, Opus 340. Toronto, ON, Elm Street Wesleyan, 2 manuals.

1864, Opus 341. Newport, RI, Belcourt Castle (Tinney Estate). 2 manuals. 22 stops 26 ranks.

1864, Opus 341. Providence, RI, Brown Street Baptist. 2 manuals. 27 registers.

1864, Opus 342. Burlington, VT, First Baptist. 2 manuals. 19 ranks.

1864, Opus 343. Decatur, IL, First Baptist. 1 manual. 12 registers.

1864, Opus 346. Troy, NY, Second Street Presbyterian. 3 manuals. 39 registers.

1864, Opus 347. Sacramento, CA, Congregational. 2 manuals. 20 registers.

1864, Opus 348. Taunton, MA, Unitarian. 2 manuals. 32 registers.

1864, Opus 349. Boston, MA, South Congregational. 3 manuals. 58 registers.

1864, Opus 350. Waltham, MA, Roman Catholic. 2 manuals. 22 registers.

. . .

1872, Opus 625. Glenville, NY, Reformed, 1 manual, 10 stops.

(after this E & G G Hook merged with Hastings)